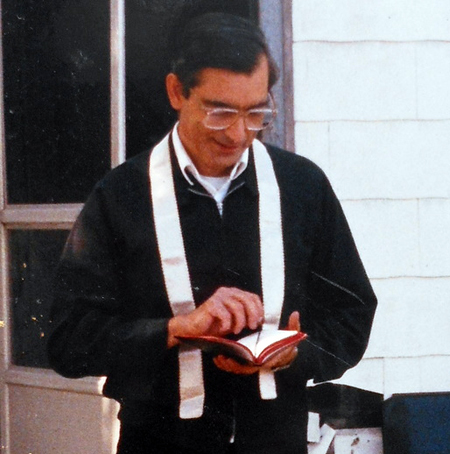

Emmanuel M. Carreira, S.J.

"YOU SHALL LOVE THE LORD, YOUR GOD, WITH YOUR ENTIRE WILL, WITH YOUR ENTIRE HEART, WITH ALL YOUR STRENGTH". Thus begins the Law with the first of the Ten Commandments, and Jesus answers with its quote the question of the Doctor of the Law who asks about the most basic and important commandment. He then adds the second one -love of the neighbor- but even if I were the only inhabitant of the Universe, without neighbors, the first precept would still be present with its full impact. It is the response due to the infinite Love of a Creator who gives me existence by pure selfless generosity, because He wants me to partake of his own life and limitless happiness.

God does not love us because we first loved Him, but the opposite is true: He has the eternal initiative to love me, because HE IS LOVE. True love seeks nothing but a return of love as its reward, in a relationship of affective intimacy that in our human experience has clear effects even upon our bodily feelings, thus giving rise to the universal symbolism of the heart to talk of that mutual self-giving, that admits no temporal or other restrictions if it is real love.

This is the most profound meaning of the concept of Religion, the "religare" -"tie together"- in a bond that is more powerful and stronger than any juridical contract or material link. We are talking about a personal relationship that springs from the very definition of Man as the living "Image and Likeness" of the Creator, and thus a "son" in an analogical but true sense. We are speaking of something deeper than any philosophical system or code of ethical norms, even if there are obvious consequences in both fields.

Christian Theology discusses three "Theological Virtues" as three steps by which intimacy with God can be obtained and its consequences influence our attitude toward Him and also our personal life. Faith as a virtue begins with the historical knowledge of Christ and his teaching, it is then received in Baptism as a gift from God that makes Him actively present by Grace, and thus constitutes like a graft of divinity by which all my acts, in keeping with the divine will, acquire an eternal value to share in God's life and happiness. The virtue of Hope adds the note of optimism and confidence in the Father throughout my entire earthly life. And "Charity" (that here means LOVE, not charitable works) expresses that union of wills required by the First Commandment. In the words of St. Paul (1 Cor. 1,1-13) if charity is absent, everything else is valueless in God's appraisal, even the generous gift of all personal possessions to the needy or the acceptance of death: all that will be judged just as noise that resounds impressing the world. Only Charity is everlasting, after Faith has been surpassed by the direct vision of God and Hope has attained every possible good.

Both in Latin and Greek -and also in Spanish- we find two different terms to indicate the affective tie, something that is lost in English. In this language the word LOVE is used to cover the entire gamut of being interested in something, appreciate a food or a sport or a work of art, a personal friendship, family relationships and even the affective response to God. To love and to like are similar. In the other languages we can distinguish two terms: in Spanish "amar" and "querer", in Latin "amare" and "diligere", in Greek "agapao" and "fileo". Neither of them can be understood as simply a degree of liking.

We can use Spanish as a modern example. Amor carries mostly a connotation of a solemn commitment typically leading to marriage, and it is also used in a more poetic language. From "querer", cariño suggests the confident attitude of a child, and it is the normal use of those terms that every day expresses the closeness and happiness of parents and children. A mother can say to a child "Come to me, my amor", but she will then say "Te quiero" and ask "Me quieres mucho?". These words are a constant part of the family exchanges that tell of the mutual attraction that gives a sense of well being and joy, that touch the heart. Perhaps the English expression "a person very dear to me" best conveys this meaning.

It is also surprising, for those who learn Spanish as a foreign language, that "querer" has the connotation of "wanting", of possession and need. "What do you want?" is translated as "Qué quieres?", a clear suggestion that the expression "te quiero" adds to the affection the mutual dependence of those whose love requires the psychological union.

When Christ teaches that we should love our enemies (Mt. 5, 44 and similar texts) He cannot ask us to feel towards them the affection that grows from a close togetherness, from exchanging smiles and sharing pleasures and a happy life. He asks that we desire for them every good thing, that we pray to God for them, hoping to have them as companions in eternal life. It would be to twist the meaning of words to say that somebody is a "friend" if I never met the person and I find a name at random in a phone book. But it is possible to love every human being on earth as God does, even sinners and those who don't know Him or deny Him: He wants their conversion and happiness. Only this love is psychologically possible, with the help of God's grace that overcomes our instinctive rejection and even the desire of vengeance, but the feeling of affective closeness is beyond our control.

In the history of religions only Christ established as the basis for his following and salvation a personal attitude of love for Him. It is this love that is shown in doing what He commands, even to the point of accepting death. It must prevail upon the most sacred family ties, love of one's parents. It will not be love in an abstract sense, that means considering Christ as the supreme norm for individual life, but rather a closeness of deep friendship, with a full impact upon our daily life, not just in a college classroom. The woman who washes and anoints Christ's feet has her many sins forgiven because of her great love. And the triple denial of Peter is erased by his triple profession of love.

It is really touching, and deeply human, the scene of the encounter of the risen Christ with Peter, when Peter's primacy is confirmed. Christ begins addressing Peter with a formal and solemn language, even asking Peter to compare himself to the other Apostles, just as he had done at the Last Supper ("even if all others deny you, I will not"). Poor Peter has learned the lesson of his own weakness, and he will not claim to be better than anybody else. But he is sure -in the deepest level of his soul- of one thing: he will never accept being away from Christ, that his heart would break in pain if he were to lose his intimate closeness. Thus, to the question: "Do you love Me more than these others?", humbly and ashamed of himself he can only answer -in spite of everything- "You know that you are dearest to me". In Greek, Christ asks "agapas me?" and Peter answers "Filo se".

The question is again repeated exactly, and also Peter's reply. But the third time Christ comes down to the family level of Peter's answer and he asks: "Peter, am I dear to you?" (in Greek: "fileis me?"). Peter cannot support that his affection be questioned, and he appeals to Christ's infinite knowledge: probably with tears and a broken voice he replies: "Lord, You know everything, you know that you are dearest to me!" ("filo se").

In this exchange the intimate friendship is restored, with an affection that was never lacking even when the fear of that painful night of Christ's imprisonment had obscured it. Christ again establishes Peter as head of his Church, a preeminence that John respected waiting for Peter before entering the empty sepulcher, and that also the other disciples acknowledged implicitly when they stated -as the best proof of the Resurrection- that the Lord had appeared to Peter. As a consequence of that intimate affective love, Christ entrusts to Peter the care of his flock: the lambs (a symbol of the new Christian faithful still in a period of growth) and also the sheep, whose deeper formation must render them fruitful to bring other members to the total Mystical Christ. An only flock with one shepherd, the vicar on earth of the only true Shepherd whose life is shared by all of us. This is the dignity of the Pope as "the servant of God's servants", whose full activity must be rooted in love, in the affection of intimate closeness to Christ.

Holiness is impossible without this personal relationship to Christ. He said, describing the final judgment, that even workers of miracles would be rejected because they lacked the union with Christ that is the meaning of true love: miracles do not imply sanctity in the miracle worker, but only mercy and power in God in whose name they are performed. In the words of St. John of the Cross, "in the evening you will be examined about your love" and there will be "many who were considered last who will be exalted as first" because they had great love. Only God knows how much love He receives from many humble children of the Father to whom they consecrated their entire life in the hidden recesses of cloistered prayer, in small towns forgotten throughout the world, in states of physical pain with the suffering Christ.

The ideas expressed so far should not be interpreted as a lack of appreciation for the help we give to others in need, be it due either to the lack of material resources or to any type of oppression or injustice. Christ replied to the question about the first commandment adding also the second, that cannot be but a consequence of the first if a true love of God and Christ includes his Mystical Body, all of God's children. In the words of John in his first letter, "whoever does not love the neighbor whom he sees cannot love God whom he doesn't see". But this helping love, expressed in beneficent works, cannot be the first: it must flow from the love of God to rise above simple philanthropy, appreciated as a human response to need, but independent of Christ's love.

I came across a statement by a Liberation Theology author where he tells of asking the Dalai Lama what religion did he consider as true. His answer had been "the one that leads us to help others". And that theologian accepted the answer as very wise and deep! But Theology cannot be equated with an Ethics of mutual help nor with a philanthropy that leaves private activity free from any other norm than avoiding injury to others. The first requirement of any religion has to be the acceptance of our dependence from the divinity, and Christ's coming into the world would be useless if it were reduced to a stimulus for beneficent work. Ethical norms imposing a duty to do good and to help those in need were found in other cultures and religions since we have references to ancient ways of acting.

The Revelation of God's intimate life in the Trinity, the painful Redemption accomplished by Christ, his Resurrection as an opening to our eternal life, Baptism and the Eucharist, are not peripheral considerations to be judged as having a lower value when compared to beneficent activities performed even by those who declare themselves to be polytheists or atheists. It is true that only Christian religion has a record of helping the neediest that cannot be compared to any other attitude in human history. It should be so, and "the poor will always be with us", just as Christ said when defending the woman who was criticized for anointing His feet. But He appreciated that homage of respect and love, and He still appreciates whatever is offered to Him even in the loneliness of cloistered life. The Church who proclaimed St. Francis Xavier as patron of the missions for his heroic activity in the Orient, also declared as co-patron St. Therese of Lisieux, who offered her hidden life of prayer and love to bring upon missionaries and their listeners the divine graces that made possible the growth of Christ's Mystical Body.

Those of us privileged to be called to the priesthood, either in the parish ministry of a given diocese or in other activities more or less directly visible as an apostolate, must never forget that our work will be mere show if it doesn't sprout from a constant union with Christ. A daily Eucharist will be the best service we can offer to the entire Church and to the faithful with whom we work, together with the Sacrament of forgiveness and the consolation of the sick. In our homilies and other suitable opportunities we can promote the beneficent work of other persons, thus adding to our own limited personal efforts the fulfillment of Christ's injunction "shepherd the lambs and the sheep". In that we follow also the example of the Apostles, who ordained deacons for tasks that were an obstacle to their own need to proclaim the Gospel.

We must apply to our vocation the norm given by St. Paul: "Pray unceasingly!". It is obvious that this cannot mean the constant recital of formulas we learned a long time ago, nor a multiple variety of devotions that may be popular at a given moment or at some place. To pray, as defined by St. Therese of Avila, should consist of "being alone with the One we know loves us", without many wordy sentences or an abstract theory fit for a classroom. Christ told us that we shouldn't talk a lot, because the Father "already knows what you need". It is said that St. Thomas Aquinas confessed that he would trade all his science for a devout "Hail Mary": any degree of closeness to God is more valuable than human wisdom.

We could say that constant prayer must be like breathing, an almost instinctive way of being affectively in God's presence, while we go about all our tasks as required by our human condition. We could use as an example the way things occur in a family: a child comes home from school and runs to kiss the mother. Then it might be time to study or to play, even with friends, not thinking explicitly about the mother's presence, but just happy to know that she is at home. Something similar might describe the atmosphere of prayer in our daily life, with some moments of more explicit awareness when we ask for help in some difficult task, or we look at a favorite religious image, or if we simply address the Lord or his Mother with a happy "I love you", perhaps to ask for help for somebody who calls because of a need for encouragement.

When we meditate upon Christ's hidden life -almost the entire span of his earthly sojourn- we must theologically accept that his growing up, learning and working in a forgotten village, in a Palestine without wealth or true political or economic independence, was as much a part of his redeeming work as his Passion, Death and Resurrection. At each stage, He was doing perfectly the will of the Father. Mary was not in a mystical rapture when she went about cleaning the house and preparing the simple family meals: she was also doing perfectly the divine will, in a spirit of love for the invisible God and for the Son received from Him. God is Love, and He knows our limitations and that we cannot think of several things at once. Christ is not a demanding taskmaster, but a true constant friend, our brother, like us in everything except sin. The simplest recipe for holiness is to follow his example: "What would Christ do in my place?".

It has been said that a priest has been "expropriated for reasons of the common good". He must relinquish his peculiarities, his personal concerns, and live for the Church. This is one of the reasons for the celibate life, even if a secondary consideration after the requirement for a total love for Christ and the example of his life as a model of total dedication to the work of salvation. The priest is not a paid bureaucrat, but "another Christ", transparent to the redeeming presence of the One who chose him as an intimate friend: "You have not chosen Me; it is I who have chosen you". "I did not call you servants, but friends" (Jn., Last Supper).

In the poetic words of J.L. Martin Descalzo (The Testament of the Lonely Bird) there is a sonnet describing how his life, especially his priestly life, was changed from trying to be a saint in "his own way" to accepting defeat and thus succeeding: "When you put an end to my journey / I will be You, living in a new way". The classical statement that love happens between equals or makes them equal, is thus fulfilled. The first Commandment does not mean an injunction to "do" something, but rather to "be" in a new way. There is nothing like it in any mythology or human philosophy.

Top of Page

Back to Emmanuel M. Carreira, S.J. essays

Back to Cleveland Catholics |